Diagrams of Theory: Parsons' and Merton's Typology of Deviance

>

Parson’s and Merton’s Typologies of Deviant Behaviors #

[

>

](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Talcott_Parsons_%28photo%29.jpg)

Talcott Parsons

In nearly every undergraduate sociology course, we discussed the mid-century sociological tradition “structural functionalism.” But, for me at least, discussions of Talcott Parsons, the theoretical powerhouse that spearheaded the rise of structural functionalism, was strangely absent. This may have been a result of the particular theoretical commitments of my teachers, rather than a true generalization of American sociology broadly. I encountered Parsons much later, and primarily as a foil against which “good” theory is measured. Nonetheless, Parsons trained some of the foremost theorists, including Robert K. Merton, who later become a critic of Parsons’ grand theorizing.

Merton’s Typology of Deviance predates Parsons’ own, however, the latter considers Merton’s theory to be a “very important special case” of his own general theory of action. In Sociological Theory - A Contemporary View: How to Read, Criticize and Do Theory (which, I highly recommend for those who wish to do theory), Neil Smelser (also a student of Parsons) directly compares and critiques the two theories of deviance.

Merton hinges his typology on the notion of “anomie,” which he defines as the misalignment of cultural goals with institutional means. Although Merton theorizes within the tradition of structural functionalism, he recognizes that the operation of different social systems is not inherently beneficial to the functioning of society as a whole.

>

Merton’s Diagram of Typologies of Deviance

>

Robert_K_Merton

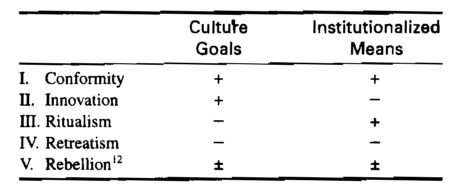

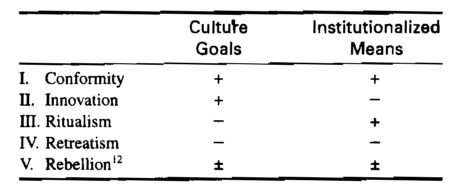

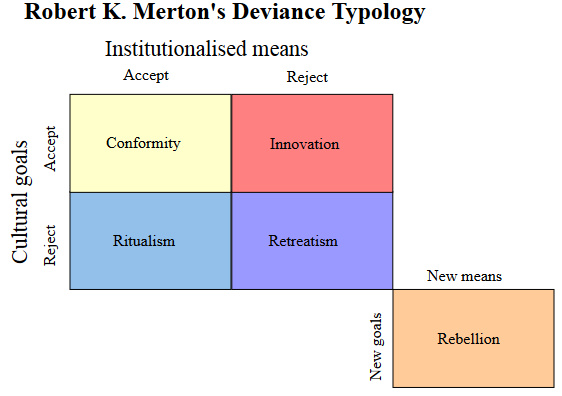

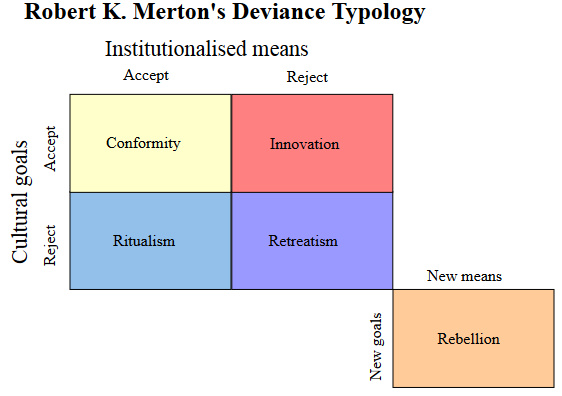

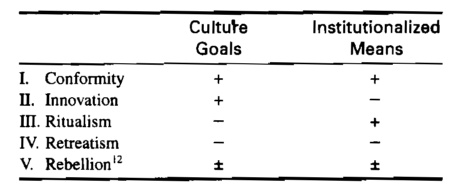

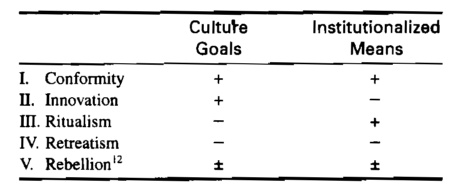

People may accept cultural goals and the institutional means, however they might reject one or both (indicated by a + or - in the table below). This creates the fourfold grid above: Conformity, Innovation, Ritualism and Retreatism. It is also possible that instead of rejecting both goals and means in a particular situation, people may actively create new goals and means: Rebellion.

>

Robert Merton, Typology of Deviance (1938)

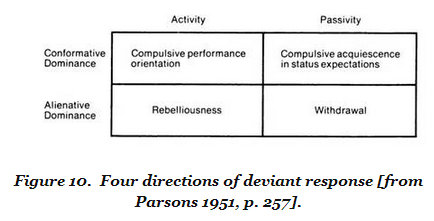

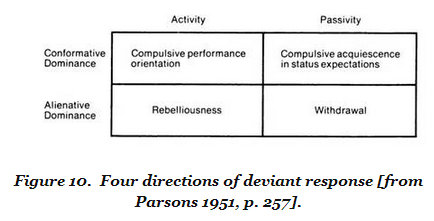

Parsons attempts to integrate his own general theorizing with the “middle range” or “special case” of Merton’s. Where Merton considers deviance to be a response to “anomie,” Parsons considers deviance to be but one possible response to “strain.” Similar to anomie, strain results when there is a misalignment between expectations and behavior. That is, when someone else does something that I don’t expect. (Although deviance may in turn cause strain, they are two distinct concepts). Not all strain results in a deviant response, and Parsons outlines several possible alternative reactions to strain. Like Merton, if strain results in a deviance, the person is likely to respond with general ambivalence (leaning toward conformity or alienation), and they may respond passively or actively. Combining these dimensions results in a fourfold typology reminiscent of Merton’s.

>

Parson’s Fourfold Typology of Deviant Responses

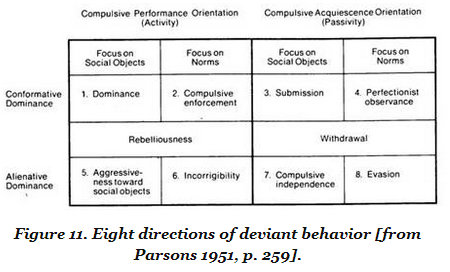

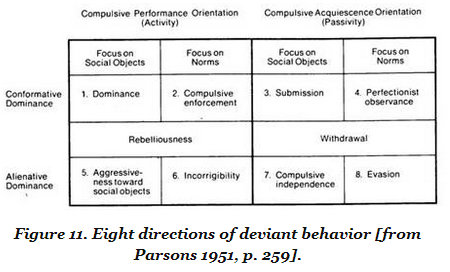

Parsons adds one more dimension to create the eightfold typology below. A person, responding deviantly, may direct their actions toward people (or social objects) or toward norms.

>

Parson’s general typology of deviant behavior.